In the Wind of Time The history of windmills on Fuerteventura

Once upon a time, there was an island – barren, windswept and full of silence: Fuerteventura.

People lived simply, closely in tune with nature’s rhythm, and the wind was their constant companion.

What today’s visitors experience as a pleasant breeze was, for the locals, an invisible workmate – and eventually their most important source of energy.

People lived simply, closely in tune with nature’s rhythm, and the wind was their constant companion.

What today’s visitors experience as a pleasant breeze was, for the locals, an invisible workmate – and eventually their most important source of energy.

Long before wooden blades reached for the sky, people ground their grain laboriously by hand.

Grinding drums made of volcanic rock – “molinos de mano” – could be found in every kitchen, and preparing gofio, the roasted grain flour, was a job for strong arms.

Those who had a bit more would use a “tahona”, a stone mill powered by animals, which turned slowly in tedious circles.

Grinding drums made of volcanic rock – “molinos de mano” – could be found in every kitchen, and preparing gofio, the roasted grain flour, was a job for strong arms.

Those who had a bit more would use a “tahona”, a stone mill powered by animals, which turned slowly in tedious circles.

But the population grew, demands increased – and the wind was always there. Constant. Tireless.

In the 18th century, the first windmills began to rise above the island’s sparse landscape.

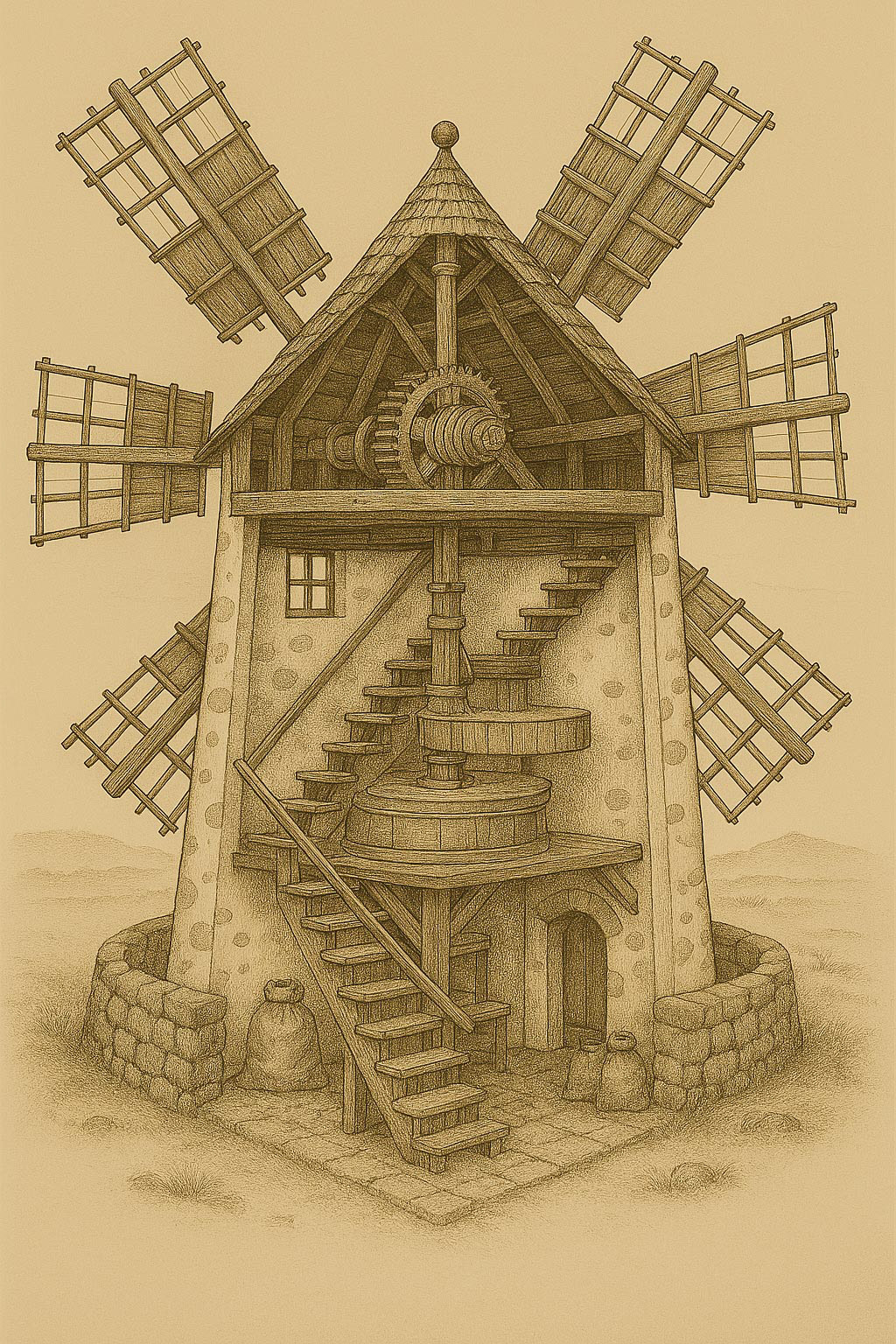

Stone by stone, wooden beams for the roof, a mechanical heart of gears, shafts, and millstones – born of necessity, shaped by Spanish influence, and inspired by North African design.

Stone by stone, wooden beams for the roof, a mechanical heart of gears, shafts, and millstones – born of necessity, shaped by Spanish influence, and inspired by North African design.

At first, they were round molinos with a tower and an upper floor for the milling mechanism.

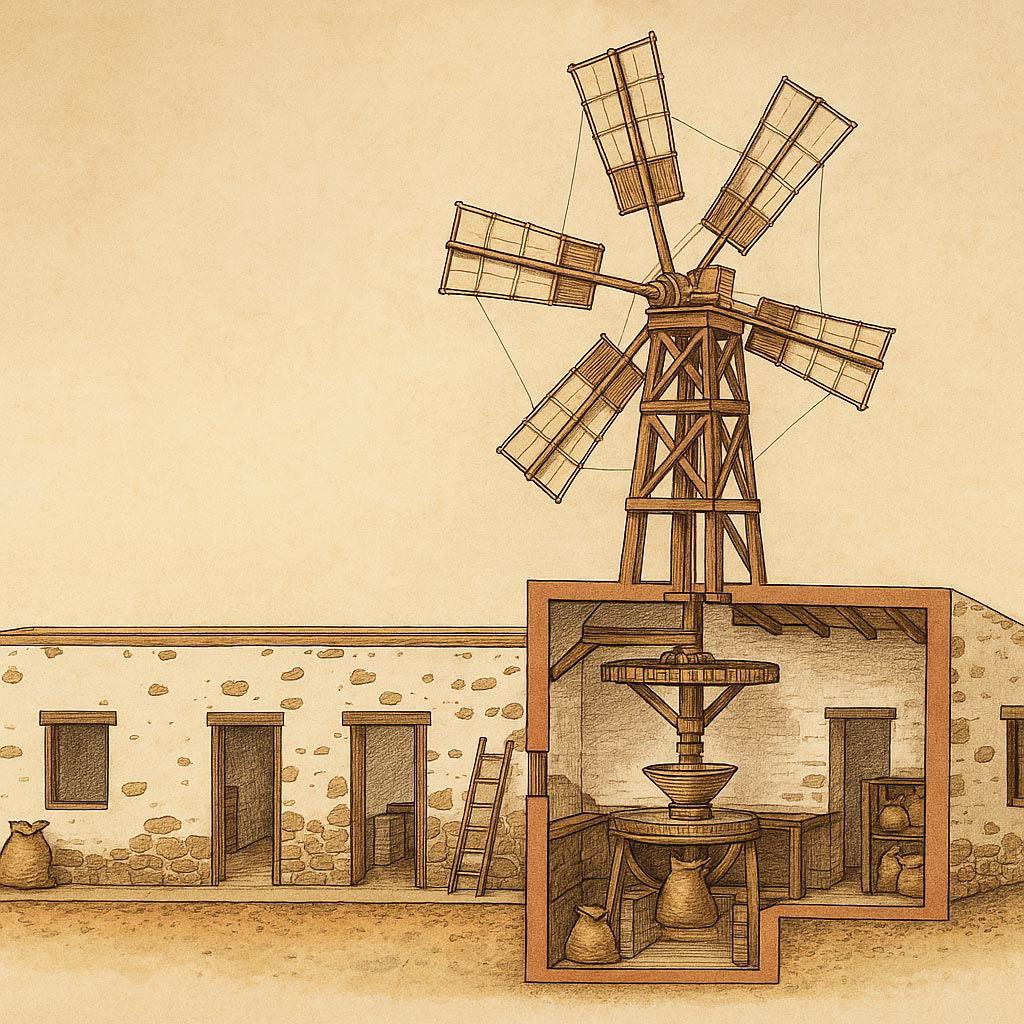

Later came the molinas – lower in height but cleverly arranged. These new mills used the wind just the same, but the miller now worked entirely in the lower room: setting the sails, feeding in the grain, packing the flour – all in one place, efficient and refined.

Later came the molinas – lower in height but cleverly arranged. These new mills used the wind just the same, but the miller now worked entirely in the lower room: setting the sails, feeding in the grain, packing the flour – all in one place, efficient and refined.

The miller was not just a craftsman – he was a tinkerer, weather expert, and mechanic all in one.

He understood the moods of the sky, knew when the wind was strong enough or starting to shift.

Early in the morning, he checked the sails, inspected the bearings, ready to start the day with the wind.

He understood the moods of the sky, knew when the wind was strong enough or starting to shift.

Early in the morning, he checked the sails, inspected the bearings, ready to start the day with the wind.

Farmers brought their heavy sacks to the mill, often on donkeys.

There was laughter, trading, and storytelling – the mill was not just a workplace, it was a meeting point.

And while the millstone turned and crushed the grain, the air filled with the scent of freshly roasted gofio and a fine mist of flour dust.

There was laughter, trading, and storytelling – the mill was not just a workplace, it was a meeting point.

And while the millstone turned and crushed the grain, the air filled with the scent of freshly roasted gofio and a fine mist of flour dust.

Windmills were not just technical structures – they were lifelines.

Without them: no gofio, no bread, no everyday life. They set the rhythm of the villages.

If the wind was strong, the day started early – because then the great wheel turned, and work began.

Without them: no gofio, no bread, no everyday life. They set the rhythm of the villages.

If the wind was strong, the day started early – because then the great wheel turned, and work began.

For many families, the mill was a place of survival.

Those without their own grain helped with grinding or repairs, or brought goat cheese to trade.

The mill was a hub of economy, a social stage, and a technical marvel all at once.

Those without their own grain helped with grinding or repairs, or brought goat cheese to trade.

The mill was a hub of economy, a social stage, and a technical marvel all at once.

The Change

Over time, new machines, ideas, and tourists arrived.

The wind, which for centuries had faithfully and reliably served as a working companion, was now seen as a disturbance. Everyday life became more efficient, faster, and more soulless. The mills fell silent. Their sails succumbed to the weather, their stonework crumbled in the salty air.

The wind, which for centuries had faithfully and reliably served as a working companion, was now seen as a disturbance. Everyday life became more efficient, faster, and more soulless. The mills fell silent. Their sails succumbed to the weather, their stonework crumbled in the salty air.

But we never forget them. Today, many of them still stand in the landscape – silent witnesses of another time.

Sought-after photo subjects for rushed tourists. Once upon a time, there was an island where the wind shaped life, and the miller was the conductor of this dance – and life still followed the rhythm.

Sought-after photo subjects for rushed tourists. Once upon a time, there was an island where the wind shaped life, and the miller was the conductor of this dance – and life still followed the rhythm.

The Traditional Windmills of Fuerteventura

The windmills on Fuerteventura are not only impressive historic structures, but also masterpieces of traditional engineering that give the island its unique character. Each mill consists of several essential components:

Tower / base structure

The foundation of the mill, made of solid stone or brick, supports the entire structure. The tower allows the mill to harness the wind effectively while providing stability.

Rotating mill dome (molino)

The upper part of the mill rotates according to the wind direction to align the sails properly. This mechanical system allows the mill to face the wind efficiently and is a precise example of the engineering knowledge of the past.

Wind blades / sails

The large, shovel-like blades catch the wind and convert its energy into rotation. They are the central element that brings the mill to life.

Wind shaft and gear mechanism

The wind shaft transfers the rotational movement of the sails to the gear mechanism, which then drives the millstones inside the mill.

Milling chamber

In the milling chamber, grains are ground into gofio – a traditional Canarian food that forms the basis of many local dishes.

These windmills are a fascinating example of engineering and a symbol of Canarian culture. For centuries, they provided the energy needed to process grain on the island.

The Traditional Milling Process of Fuerteventura’s Windmills

When the wind sweeps across the hills of Fuerteventura, it carries echoes of a time when its force meant not only weather, but also work. The island’s traditional windmills were once the core of a finely tuned process in which nature, technology and craftsmanship worked hand in hand. For centuries, they shaped the island’s food supply, daily life, and identity.

The entire process – from harvest to finished product – can be broken down into several key steps:

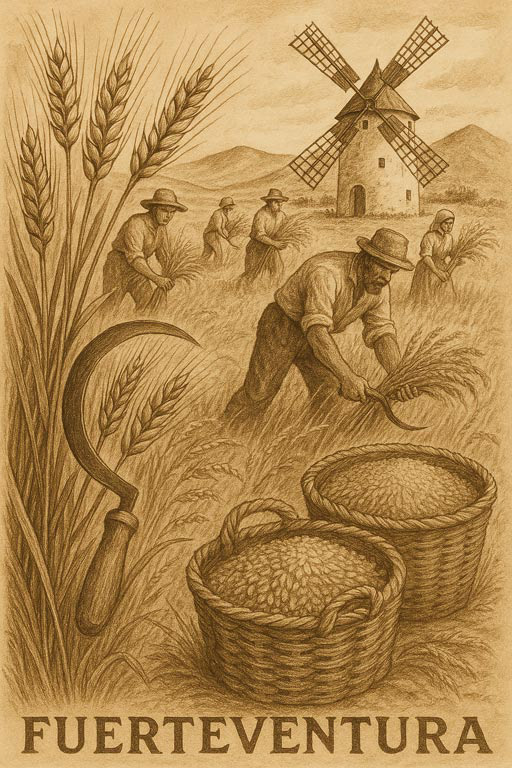

1. Harvesting and Preparation

– Selecting and harvesting the grain

At dawn, farmers would move through the fields armed with sickles, the rustling of grain in the wind marking their rhythm. Wheat and barley were the most commonly cultivated crops on the island’s fertile soil. The strongest plants were carefully selected and cut by hand – a laborious yet central task in agriculture.

At dawn, farmers would move through the fields armed with sickles, the rustling of grain in the wind marking their rhythm. Wheat and barley were the most commonly cultivated crops on the island’s fertile soil. The strongest plants were carefully selected and cut by hand – a laborious yet central task in agriculture.

– Drying and cleaning the grain

After harvest, the grain was spread out on large cloths or stone surfaces to dry for several days under Fuerteventura’s hot sun. The kernels were then cleaned of dust, husks and foreign matter – a process that greatly determined the quality of the final product.

After harvest, the grain was spread out on large cloths or stone surfaces to dry for several days under Fuerteventura’s hot sun. The kernels were then cleaned of dust, husks and foreign matter – a process that greatly determined the quality of the final product.

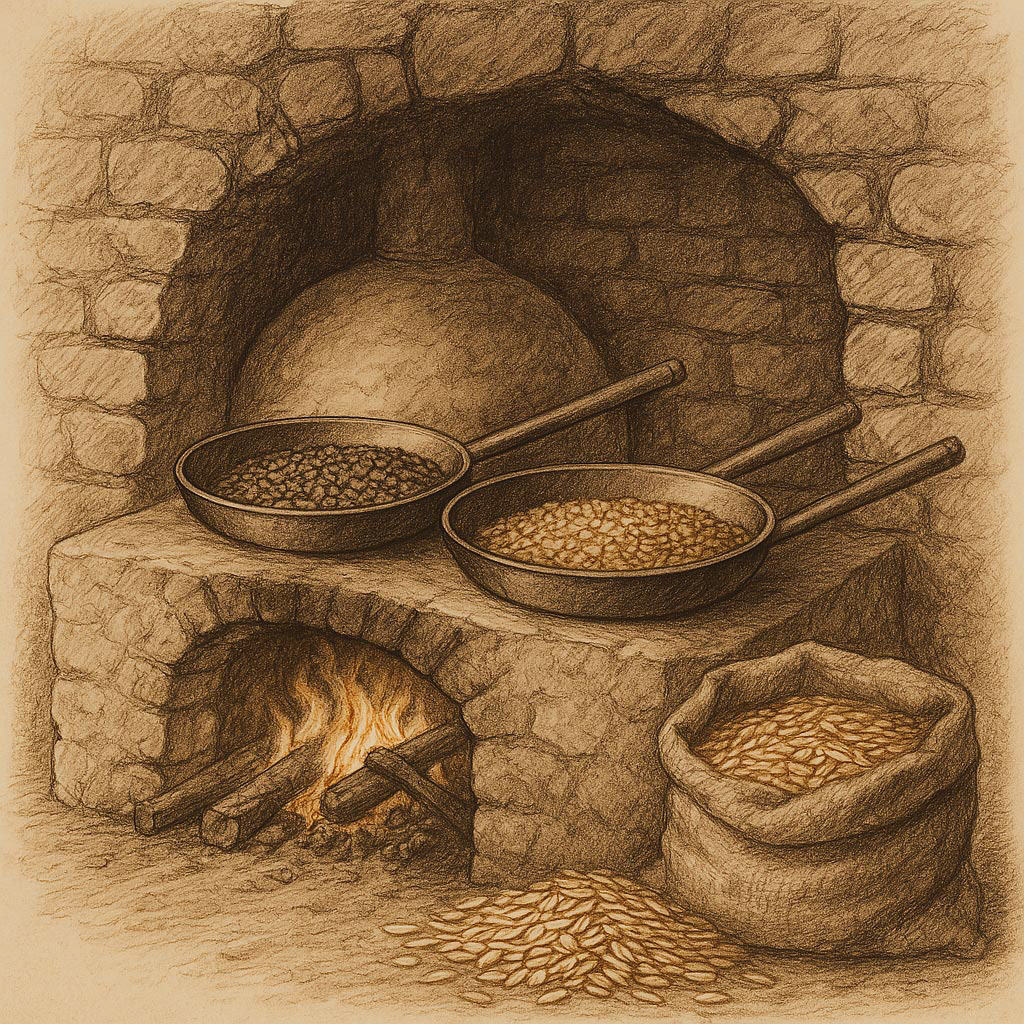

2. Roasting

Roasted grains became the aromatic heart of the later production. Stirred constantly, they were heated in open clay pans or directly over fires inside the mill.

A nutty, slightly smoky scent filled the air – the unmistakable aroma that would later define gofio. Roasting not only improved the flavor, but also extended the shelf life of the flour – a vital advantage in dry months.

A nutty, slightly smoky scent filled the air – the unmistakable aroma that would later define gofio. Roasting not only improved the flavor, but also extended the shelf life of the flour – a vital advantage in dry months.

3. Grinding

– Wind-powered mills

When the wind picked up, the mill’s sails began to turn. The mill’s top – the rotating dome – was adjusted to best capture the wind. This set the wooden gears into motion, driving the heavy millstones. It was a harmonious interaction between the power of nature and human engineering.

When the wind picked up, the mill’s sails began to turn. The mill’s top – the rotating dome – was adjusted to best capture the wind. This set the wooden gears into motion, driving the heavy millstones. It was a harmonious interaction between the power of nature and human engineering.

– Coarse or fine grinding

By carefully adjusting the mill, the miller could control the grind’s texture. For gofio, the flour was often left slightly coarse, giving it its distinctive hearty character. Fine flour was typically used for bread or pastries.

By carefully adjusting the mill, the miller could control the grind’s texture. For gofio, the flour was often left slightly coarse, giving it its distinctive hearty character. Fine flour was typically used for bread or pastries.

4. Processing into Gofio

After grinding, the grain was ready for its final purpose: gofio production.

This versatile flour was used as-is or mixed with liquids like broth, milk or water. It became a nourishing porridge or dough – often hand-formed and traditionally prepared in wooden bowls. Every family had its own mixes, preferences, and rituals – gofio was more than food, it was part of cultural identity.

This versatile flour was used as-is or mixed with liquids like broth, milk or water. It became a nourishing porridge or dough – often hand-formed and traditionally prepared in wooden bowls. Every family had its own mixes, preferences, and rituals – gofio was more than food, it was part of cultural identity.

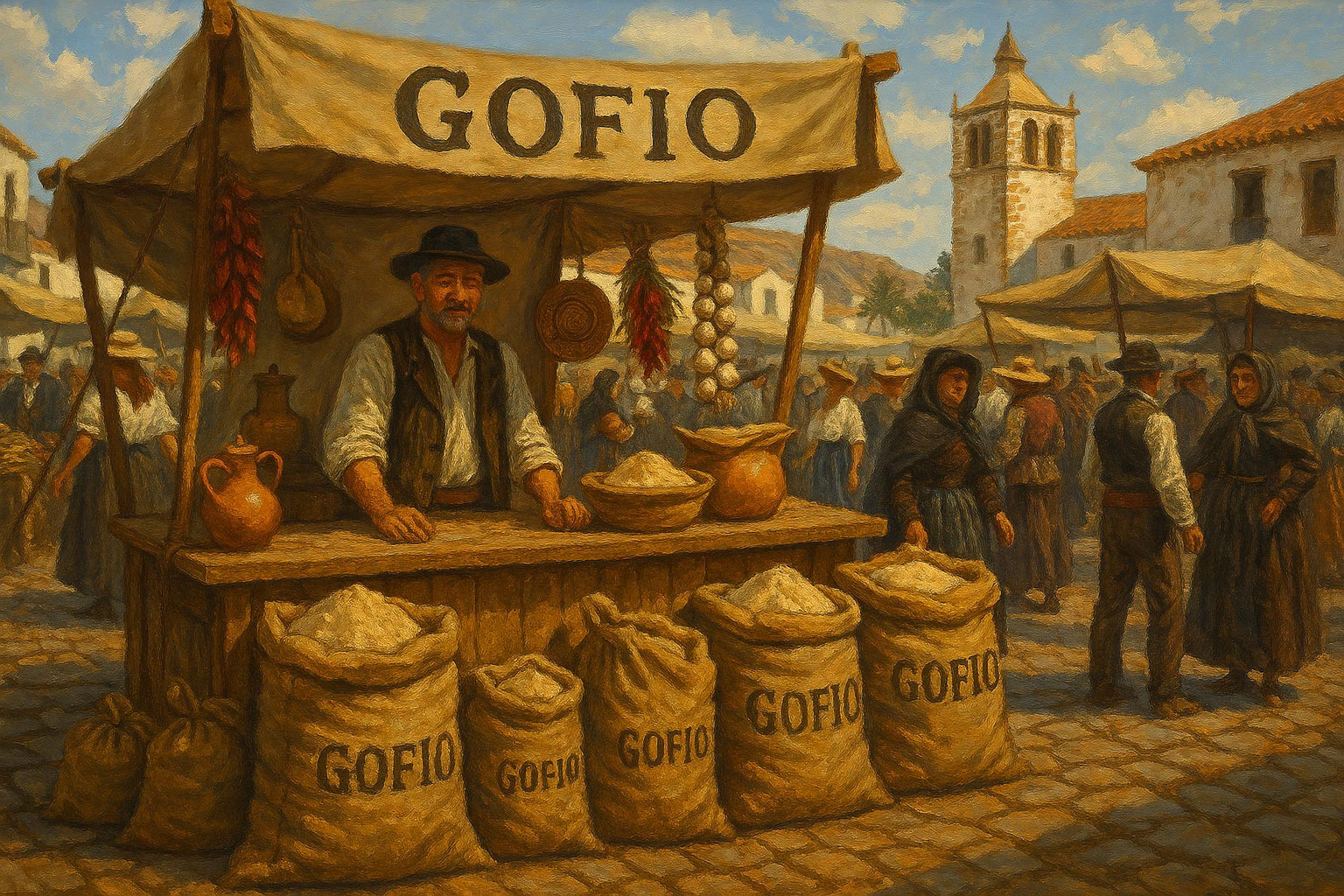

5. Trade and Consumption

– Historical trade

Gofio was a valuable commodity on Fuerteventura. Sold at local markets in jute sacks or clay jars, it was often freshly ground right next to the mill. In later years, it gained regional fame and was exported to other Canary Islands and beyond – thanks to its shelf life and nutritional value.

Gofio was a valuable commodity on Fuerteventura. Sold at local markets in jute sacks or clay jars, it was often freshly ground right next to the mill. In later years, it gained regional fame and was exported to other Canary Islands and beyond – thanks to its shelf life and nutritional value.

– Traditional and modern recipes

Once used in simple meals like “gofio escaldado” (mixed with broth) or “gofio con leche” (with milk), gofio now appears in modern recipes too – in desserts, ice creams, smoothies and even gourmet restaurants. Thus, the tradition lives on in a new form.

Once used in simple meals like “gofio escaldado” (mixed with broth) or “gofio con leche” (with milk), gofio now appears in modern recipes too – in desserts, ice creams, smoothies and even gourmet restaurants. Thus, the tradition lives on in a new form.

A legacy in the wind

Today, when the wind brushes against the silent blades of the old mills, it carries the stories of generations – of hands that harvested grain, of fires where it was roasted, and of mechanisms that turned the soil’s bounty into daily sustenance.

Fuerteventura’s windmills are more than buildings – they are silent witnesses of a time when the wind meant life.

Fuerteventura’s windmills are more than buildings – they are silent witnesses of a time when the wind meant life.